Westworld Season 2 Premiere Review

Have you ever questioned the nature of your reality? The price you'd have to pay if there was a reckoning? That reckoning is here. - Dolores Abernathy

It feels like it's been forever since "The Bicameral Mind" aired, and there's a good reason for that. The Westworld first season finale premiered on December 4, 2016. Our current President of the United States hadn't taken the oath of office yet, and a lot has happened in our world and in our individual lives since the last time we hung out with the Delos Destinations crew and journeyed into the addictive mind trip that is the Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy adaptation of Michael Crichton's story.

Generally speaking, the audience enjoyed the opening ten episodes more than the critics, as many of the latter group went out of their way to say this was by no means a great show, and often was barely a good one. If you happened to read my reviews of each installment in 2016, you'll know I diverged from my colleagues on the show, but admitted it was made for me, especially with the moral and theological questions the series presented. That remains true as the second season begins, but there's a caveat that if you watched the opener, you likely know all too well.

Those that haven't gone back and watched the first season, or at least a few of the key episodes, are going to have a difficult time remembering exactly what took place 18 months ago. This isn't a simple show, by any means, and there is very little recap given in "Journey Into Night" outside of the introductory video. You'll remember the characters and the larger plot points, but the smaller motivations and details, which feel much more important in Westworld as compared to less story-heavy shows, may be lost. My advice is to try to work the first season into the next few weeks of your viewing schedule.

It's worth the time, because if the opening of Season 2 is any indication, this is going to be a boatload of fun. It's potentially even more confusing and headache-inducing than ever before, and we'd want it no other way. Not everything makes sense, because there's no whodunit to answer every hour before moving to the next case. This is a glorious mess, imperfect but visually stunning, flawed but relentlessly captivating. This is why we love entertainmen. It's challenging, but done with intent and care. Westworld's second campaign begins in a state of chaos and mayhem, and my only response is, let's do this!

As we watch Bernard Lowe attempt to piece together all of what took place the night Robert Ford and many others were murdered, Jeffrey Wright walks around with a facial expression attempting to balance concern with confusion. It mimicked my own, as his discombobulation matched up with how I felt as I stumbled around like a figurative drunkard trying to understand exactly what we were seeing. It came into focus for him near the end of the episode after the injection, and in many respects, it did the same for the viewer.

Season 1 of Westworld was dubbed, "The Maze," or it has been since the initial airing, and what we discovered in the finale was that Dolores reached its center once she evolved (her words tonight) into a being with consciousness. The voice in her head was hers, not Arnold's, as she was created to be an amalgam of him, herself, and of course, she's also the infamous Wyatt. She is the walking nuke to destroy Westworld, and she killed Ford, still believing him to be what we found out he wasn't. Arnold sought to keep the park from opening, and gave his life to stop it once he realized the implications of it all as well as his affinity for the hosts.

The revelation of William's own evolution (or devolution) into the Man in Black was by no means surprising, but in large part, what we witnessed through the first season was an awakening of self-awareness and individuality not just in the hosts, but also in the guests. He couldn't deal with an entertainment destination without consequence and where he could form an emotional attachment to someone like Dolores, but eventually she'd forget him when it was time for her loop to reset.

This was a man who spent decades seeking one woman, losing sight of the reality of the amusement park and wanting to break the fiction to uncover the fact. It's like scalping a ghost warrior, finding the maze along with the brain, and then extracting the hard drive containing the memories, thoughts, and near humanity of the bot. But, unlike his favorite roller coaster, he was never actually "upside down" on the spiral loop. There was a track, there was a loop, but his own emotions, from love to revenge, had no lasting basis outside of his own mind. But, if he could unlock Westworld's secrets, maybe that could change. He had money and power in the real world, but as often happens, it can leave one emptier than another with no bank account of which to speak.

We find Maeve Millay in the same state of what you could call "focused, driven madness," as she continues to search for the daughter Lee Sizemore tries to remind her doesn't exist. Between Thandie Newton and Evan Rachel Wood, whose performances both remain outstanding, the ladies of Sweetwater are by far its most dangerous and compelling residents. Season 2 of the show is subtitled, "The Door," and we see just a glimpse of what that could mean before the premiere ends.

However, if "The Maze" is any indication, we will all be speculating, only to find out we were only half-right once we place our eyes on the doorknob. That said, it can be interpreted in multiple ways based on the first 69 minutes of the season. Sure, the door for the hosts into the real world is relatively obvious, or just a door to consciousness on a larger scale. Literally, for Charlotte Hale and those like her, including a less than enthused Bernard Lowe, it's the door to get the heck out of the war zone that's erupted around them.

For Maeve, it's the door that leads to her daughter and the one loop that wasn't entirely wiped from her memories after being recommissioned over and over again like a bootlegged audio cassette from 1995. She might have lost parts of it, but some of it wasn't overwritten. It's a door to the life she CHOOSES, rather than the door she's pushed through.

For Lee, Charlotte, Karl Strand, Ashley Stubbs, and the non-human guests, it's the door to re-establish control over the lucrative enterprise, and the way back into the real world. For the first time, Westworld has stakes, which the Man in Black points out within the first few lines he speaks this season. There's now a blurred line between the park and actual society. Think of it with the above roller coaster analogy, but now realize that if there's a malfunction and the magnetism or technology fails, that ride could be fatal, rather than just thrilling.

Meanwhile, as the humans that weren't killed at Ford's narrative unveiling are searching for normalcy, the hosts, particularly those that matter to us, are...doing the same thing, but with a new addition. Dolores tells Teddy, after a soaring speech about remembering everything and knowing how the story will end, that merely claiming Westworld isn't enough. She mentions a "greater world out there" that belongs to "them." Teddy asked her who "they" were and she painted a relatively accurate portrayal, from her perspective anyway, of manipulators that took host lives and memories, controlling the A.I. slaves of the park.

Now, she not only wants their world, she needs it. The one role so many of them never asked her to play, never expected or anticipated her to play, is the one she understands. She has one character left to portray, and it's herself. The "free will" host, with no loop and no failsafe, that can Wyatt her way out of the park, past the water and into the wild blue yonder, where she presumably can take out her aggression on the public at large, is the one Bernard feared during the episode's first few minutes.

Lee tells Maeve, "Your daughter, she's just a story. Something we programmed. She's not real." Don't stop with that brief explanation as you consider it across the series. Apply it to William. "That girl you love, she's just a story. Something we programmed. She's not real." Apply it to Hale, Strand, and the humans. "That power you love, it's just a story. Something we programmed. It's not real." The money might be, but self-aware A.I. with an axe to grind reminds us that control, as Mr. Robot continually says, is an illusion.

Before he's shot in the head, the young Robert Ford asks the Man in Black what's next for him now that Westworld has real consequences for the guests, and presumably for the hosts as well. He inquires as to whether William "achieved what he wanted." Does he yearn for more? Then, as his voice glitches to remind us he's A.I., he tells the Man in Black that the new game isn't to find the center of a maze, but to find the door. "Congratulations, this game is meant for you." He finishes his cryptic commentary with a few words to tell our villain (or villainish guy that does bad things at least) the game will find him, and that "everything here is code."

That's a good way to view Westworld. The reason Lost, Fringe, and other sci-fi mystery shows generate so much interest is because the discussion never ends. People still debate the end of The Leftovers and whether or not Nora's story to Kevin Garvey was in fact, merely a story. Look at this show as you do those, where the questions might be answered, but shouldn't always be your endgame. You may be disappointed if you don't, but also remember that this is the kind of show where characters say seemingly important things that don't always lead anywhere. Occasionally as you walk through a maze or search for a door, you find dead ends and temptations that end up requiring a detour.

Peter Abernathy's role continues to grow. Dolores' father is now a Delos corporate insurance policy, and one Charlotte Hale admits the company desires to recover so badly, they'll allow every human trapped in the park to die until they find him. Incidentally, Louis Herthum has been promoted to a series regular, so his portion of the story is going to be with us for the next few months, if not far longer. Its full implications in the short-term aren't fully fleshed out, but I predict once it's all out there, it will be one of the year's highlights.

Back to the penultimate episode of Season 1, "The Well-Tempered Clavier," recall Ford telling Bernard that "free" hosts wouldn't survive. "Humans are alone in this world for a reason. We murdered and butchered anything that challenged our primacy." What we know right now is that the hosts are operating under the same assumption of themselves, and with the same lack of understanding. Here, Dolores wishes for her own freedom at others' expense, and she's as violent and sadistic as William was in response to her own memory loss.

What this means is we're about to see a more vicious, more gory, more chaotic season of Westworld. If you were one of those that lamented the slow start to the series and bailed out, you're about to get what you want. The slow-burn, at least for now, appears to be over. "Journey Into Night" was arguably too busy, too involved, and is as unapproachable for a new viewer as any series I've ever seen. Luckily, it's by design. This isn't a show you can pop into and expect to enjoy. It's one that rewards attention and recall, and often requires the rewatch to fully appreciate it.

All ten of my first season reviews are available here on the site. Just search "Westworld" and they'll come up. It's the Cliff's Notes version to recap things, and of course I was limited by what I knew at the time and the sentences are filled with theorizing. That's what will happen this time around as well. I'm going to write a lot and say a lot, some of it will make me appear to be a genius and other portions will make me seem to be a dunce. That's what makes it fun. I got some of the best email responses of my writing career during the first season, with hypotheses and critiques and theories and questions. I look forward to the same this year.

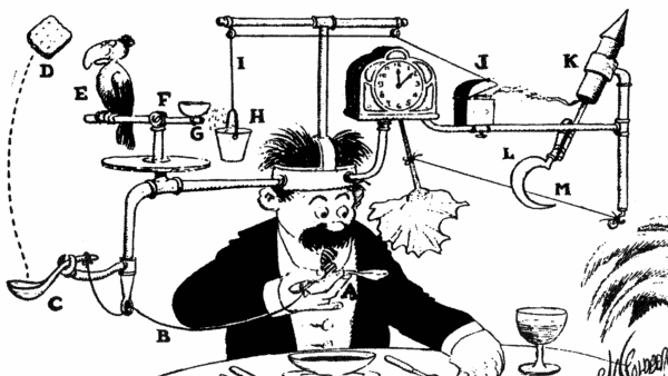

The player piano is back folks. Guess what, it's a metaphor, a self-playing machine/instrument built on redundancy to illustrate the difference between humans and technology. American inventor and cartoonist Rube Goldberg created the idea of a machine that does something simple, but accomplishes it through the most convoluted of processes. Think of Doc Brown's contraption to feed Einstein in Back to the Future, and how much went into it to accomplish one very basic task. Take the task from the film, simplify it further, then complicate the contraption, and you've got a Rube Goldberg machine.

One item is activated, resulting in an action that then turns a figurative switch on the next, eventually getting to the goal. In 1931, Goldberg drew a cartoon entitled, "Professor Butts and the Self-Operating Napkin," which is exactly what you'd think it is. But, just incase you'd rather look and not think, because your mind is exhausted from the premiere, I've got you:

Goldberg often described his Uber-popular work as a "symbol of man's capacity for exerting maximum effort to accomplish minimal results." It wasn't always sarcastic or snarky, and even today, competitions occur throughout the world as people make their own Rube machines. The Random House Dictionary in 1966 defined "Rube Goldberg" (devices and concepts) as "deviously complex and impractical."

Westworld as a whole can often fall into that classification as well, and the player piano itself fits the idea. But, like we love the contemporary or famous songs we hear in the simple saloon form, we love Westworld for the same reason. It might be a lot of work to get there, and it might take deviations that seem ridiculous in hindsight, but the chase is always better than the destination. So, we embark on this ride in the amusement park we thankfully watch from a distance.

But, the questions of consciousness, motivation, misplaced emotion, and human nature are very real, and it's largely because of those themes that I'll spill a lot of virtual ink over the next several weeks. The episode description was centered around the line, "The puppet show is over." It's about to get ugly, folks.

Was Ford a madman? Was he evil? Was he damaged? What is his master plan? Was there purpose before his peril? In the final sequence of the opener, we see dead hosts floating in the sea that appeared to come from the middle of nowhere. We also see a dead bengal tiger that seemed far away from home. Strand asks Bernard what happened. "He killed them. All of them."

And. Away. We. Go.

I'm @JMartOutkick. I don't mean anything. I'm just noise. I'm not real.