The New York Times' Exaggerated COVID, Misled Its Readers On Masks: Report

There were any number of inexcusable decisions made during the COVID-19 pandemic. Politicians made indefensible policy choices, forcing 2-year-olds to wear masks and millions to show proof of vaccination to engage in necessary everyday activities.

Those decisions were informed by "experts," who frequently made unsupported assertions and claimed to represent "science" while ignoring contradictory data and evidence. Teachers unions colluded with their political partners to keep children out of school for years, all while other countries showed that schools could open safely. There's plenty of blame to go around.

It's hard to apportion blame when there's so much of it to go around and so many people and institutions who failed spectacularly. But much of the justified ire towards those people and institutions should be reserved for the media.

After decades of eroding trust in traditional media sources, formerly reputable outlets during COVID took a blowtorch to whatever remaining shreds of credibility they had left. Few were worse than The New York Times. It was obvious to outside observers that The Times made an editorial decision to lean hard into expert-derived COVID misinformation: schools must close, masks must be worn, any and all extremism in a futile attempt to combat an infectious respiratory virus was justifiable.

Now, thanks to a new report, we have data on just how bad the Times' coverage was. And how much damage they likely caused.

Dr. Rochelle Walensky, Director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (Photo by Greg Nash-Pool/Getty Images)

New York Times Exaggerated COVID Risks, Promoted ‘Interventions’

Dr. Vinay Prasad and two co-authors recently published a new report on how the Times handled its coverage of the pandemic. No matter how bad you thought it was, the reality was somehow even worse.

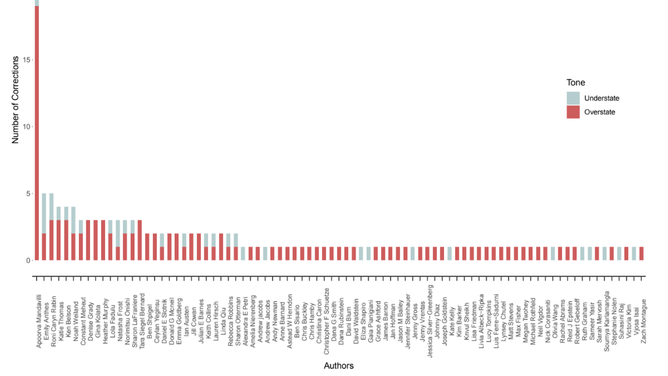

According to their report, between 2020 and 2024, on 486 articles relating to COVID, the Times issued a whopping 576 corrections. 576 corrections to 486 articles, meaning some articles, many, in fact, had at least two corrections attached.

Well that's good news, you might think…the Times got their coverage wrong, so they issued corrections to update readers when new evidence showed masks don't work, or that the risks of the virus were overblown. Right? Not exactly.

"That’s not what we found," Prasad writes in City Journal. "Instead, the paper’s errors tended to exaggerate the harm of the virus (or the effectiveness of interventions). Corrections were made for such errors nearly twice as frequently as for errors that downplayed harms. Fifty-five percent of errors overstated the harm of the virus, while only 24 percent understated (the rest were equivocal). In other words, when the New York Times got things wrong, it tended to do so in a way that falsely stoked fear and encouraged harmful social restrictions."

One of the Times' most indefensible mistakes was its work to exaggerate the risks of COVID to children. Science writer Apoorva Mandavilli was one of the papers' worst offenders, frequently getting basic facts wrong, accusing COVID critics of racism, or downplaying evidence that contradicted her opinions.

Perhaps the most extreme example of her spectacularly bad work was an article from October 2021 on the number of COVID-related hospitalizations affecting children. As Prasad's report covered, the Times was forced to issue a correction, because she exaggerated the real statistics by 1329 percent.

"An article on Thursday . . . misstated the number of Covid hospitalizations in U.S. children," the Times' correction says. "It is more than 63,000 from August 2020 to October 2021, not 900,000 since the beginning of the pandemic."

So close.

That wasn't Mandavilli's only mistake; according to the report, she was responsible for more than 7 percent of all corrections by the Times during COVID.

This is the Times' top "science" and health reporter.

Obvious Motivations For New York Times' Mistakes

The report states that the corrections led to "meaningful differences" in how readers would interpret information.

"We found that corrections made by NYT authors often led to meaningful differences in how information was portrayed, particularly when corrections pertained to COVID-19, where the original information more often overstated the COVID-19 pandemic and gave the impression that the situation was more dire than it actually was."

All too frequently, Times' reporters exaggerated COVID risks while advocating for the importance and necessity of pandemic policies. Only after the article was published and garnered attention would corrections be issued to fix mistakes. As is so often the case, the media achieves its goal of widepsread distribution with inaccurate information, while the corrections go mostly unnoticed.

Simply, "When compared to non-COVID-19 corrections, we found COVID-19 corrections were six times more likely to overstate the magnitude of the problem. In other words, when reporters erred, it was towards engendering greater fear and panic," as the report says.

Why would there be so many mistakes? What possible explanation could there be?

The Times, like most media outlets and their political partners, had an ideology that required them to believe whatever the "experts" fed them. Anthony Fauci, the CDC, the self-proclaimed arbiters of truth, told the Times what to think. And its reporters, instead of treating those claims with skepticism and verification, believed them without question.

They belong to the same subset of people; those who have the "right" ideas, who move in the same circles, share the same views. Outsiders who disagreed were dismissed as conspiracy theorists or "free-dumb" loving simpletons.

But the Times' coverage was wrong, its reporters were wrong. Their corrections showed a clear pattern of exaggeration and promotion, not a focus on unbiased accuracy. It was yet another embarrassment for a once-proud institution.